KIDS AND COACHES

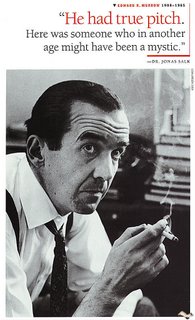

YMCA 11-12 SONICS, BOTTOM ROW: Mike Nunnally, Trevious Atkins, Tevin Mack, Laneyshia Fudge, Coach Dennis Mack. TOP ROW: Coach Jim Finkelstein, Devin Sheppard, Alex Berry, Chris Wright, Tim Pierce

The rebound came into the waiting arms of Chris Wright, who whirled and threw an outlet pass to Tim Pierce, who in turn threw a bounce pass to a cutting Trevious Atkins for the fast break layup. I turned to my co-coach and longtime friend, Dennis Mack, and said: “I feel like I’m in heaven!”

I have just completed my 15th season of coaching YMCA basketball. Years ago I used to joke that I was the worst coach in history, because I once took a team with three future high school starters- one of whom went on to play college ball- and managed to lose almost every game. But the truth is that there are intangible benefits to playing a team sport that greatly transcend wins and losses. Don’t get me wrong-- no one wants to be on a team that loses every game by a lopsided score. That’s not a positive experience for any child, and it’s a good reason why YMCA youth sports directors try to create balanced teams at the beginning of every season.

But team sports are important, both to society and to the individuals involved. As much as Americans idolize the lone hero-- including fictional characters played by John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, and Mel Gibson-- we also invest tremendous emotion in team sports. Whether it’s pro teams like the 2004 Boston Red Sox or the 2006 Pittsburgh Steelers, college teams like Texas football or Duke basketball, or local high school and youth teams, Americans of every stripe from every corner of the country take great pride and great interest in “their” teams. Two of my cousins who grew up Steelers’ fans in Western Pennsylvania, then moved to the Seattle area, were especially conflicted when this year’s Super Bowl pitted the Seahawks against the Steelers. And that’s a good thing, because not to care, not to be passionate about sports and teams, is to be deprived of one of the great pleasures in life.

That being said, there is definitely a line that is too often crossed, from the lowest to the highest levels. A referee who blew calls in an NFL playoff game being the victim of vandalism, assaults involving parents in youth sports teams, and cheating scandals from the age violations at the Little League World Series up to steroid use in track and field and Major League Baseball, are all evidence of a tragic loss of perspective.

A few years ago, after a YMCA season had ended, I received a letter from the father of one of my players. The letter writer had been one of those officious parents who would sit up in the balcony during practices and games, yelling specific instructions at his son that left the poor 9 year old completely confused as he tried to listen to both his coach on the sideline and his father in the stands, all the while paying attention to the game going on around him. During the season I had politely asked the father to refrain from yelling at his son during practices and games, and suggested that instead he spend as much time as possible working with his son on his individual skills in between practices. The father complied with my request, but apparently had some pent up feelings that he waited to express. The letter blasted me, telling me what a lousy coach I was, how I knew nothing about basketball, and how I should never attempt to coach children again.

I thought about it for a while, then politely responded in writing, pointing out that I couldn’t teach essential fundamentals like how to dribble or how to shoot during two one hour practices each week. I noted out that YMCA youth basketball wasn’t like a summer basketball camp where kids spend all day working on skills and team drills, and I let him know that I made no pretense to being a professional coach (we are all unpaid volunteers). I also mentioned that his child was no Michael Jordan-- the boy had a propensity to pick up the ball and run like a football running back, neglecting to dribble-- and suggested that he should let his child play and have fun and not make such a big deal out of winning or losing.

Three years later the officious parent was the coach of his son’s team in the same age level where I was coaching. We drubbed his team by more than 20 points, and I’d be lying if I didn’t reflect that there was some poetic justice in the outcome.

Every year, I start off with the same speech. I tell the boys (and occasional girl) that I can’t teach them how to be great players, but I will give them an opportunity to learn some fundamentals of playing as a team. I tell them that they will practice good sportsmanship, winning or losing with class, and that hopefully they will bond with their teammates and make some new friends. And I let them know that they will have fun. Because the minute it stops being fun, then we have failed as parents and coaches.

This year we started with nine kids (eight are pictured) who barely knew each other, if at all. By the end of the season they had had more than a few moments of beautifully choreographed teamwork, as each helped out the other, each looked to pass to the open man, and each delighted in the success of his or her teammates. We lost two and won four during the regular season, and in the playoffs we finished second in the six team league. But in the end, all of us were winners.